LATEST NEWS

The Vikings Hockey Team Wins The Middle School Championship

By Cole McDonnell The Port Washington/Manhasset/Herricks Vikings won the NYIHSHL Middle School Championship on March 26, 2024. They beat the Massapequa Chiefs 7-1 in dominant fashion. The Vikings went 15-2-1

Manhasset Students Shine Light On The Symbols Of America

Supervisor DeSena Meets With Manhasset High School Social Studies Honor Society

Manhasset Students Traveling To International Science And Engineering Fair

Town Officials Stand In Support Of Kyra’s Law And Raise Awareness To Prevent Child Abuse

Daughters Of The American Revolution Visit Historical Society

Adventures In Learning Holds Spring Soirée

Girls Giving Back: American Legion Junior Auxiliary

Supporting vets and their families When people think of the American Legion, they might conjure images of people marching in parades or consider their numerous

Manhasset Public Schools Launches Community Poll For New Team Name

As part of its next step in identifying a new team name as mandated by Part 123 of the New York State Education Department Commissioner’s

Camera Club Keeps On Clicking

Companionable, creative outlet for over 50 years The Manhasset Great Neck Camera Club has been around since 1951, and has been meeting at the Manhasset

Tower Foundation Continues Its Mission

Manhasset alumni raise money for school initiatives The Tower Foundation of Manhasset, Inc. is a non-profit organization established in 1991 by members of the Manhasset

Manhasset Library Trustee Meet The Candidates Night April 10

On Wednesday, April 10th, The League of Women Voters is moderating a Meet the Candidates Night for the two nominees who are running for Library

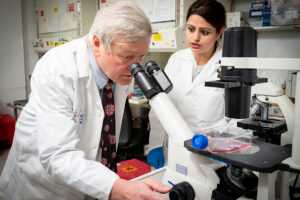

Endometriosis Study Enters Phase 2

Science is inching closer to understanding complex condition March is Endometriosis Awareness Month – a condition that affects 1 in 10 women. With little known

TRENDING

(Photo from NBCUniversal)

Chuck Scarborough:

A Beacon of Journalistic

Longevity

By Christy Hinko • April 22, 2024

THIS WEEK'S

SPECIAL SECTIONS

UPCOMING EVENTS

- Check back here for future events